Report: Rethinking Urban Planning in Detroit

Editor’s note: The following is the sixth chapter of Urban Policy 2018 published by the Manhattan Institute.

Introduction

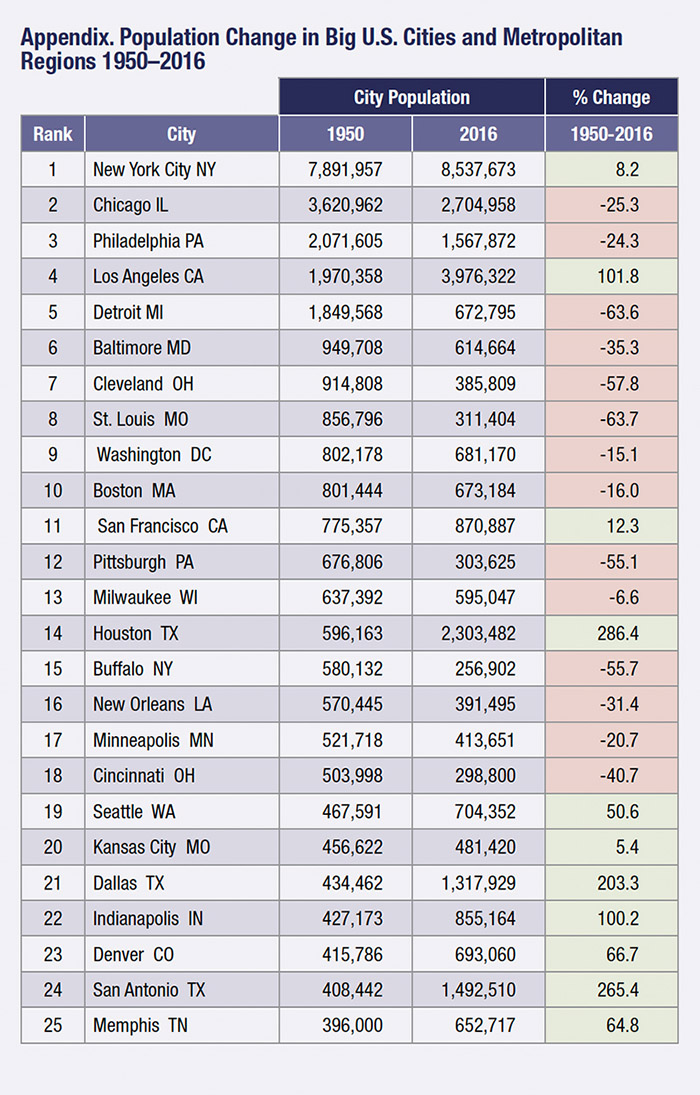

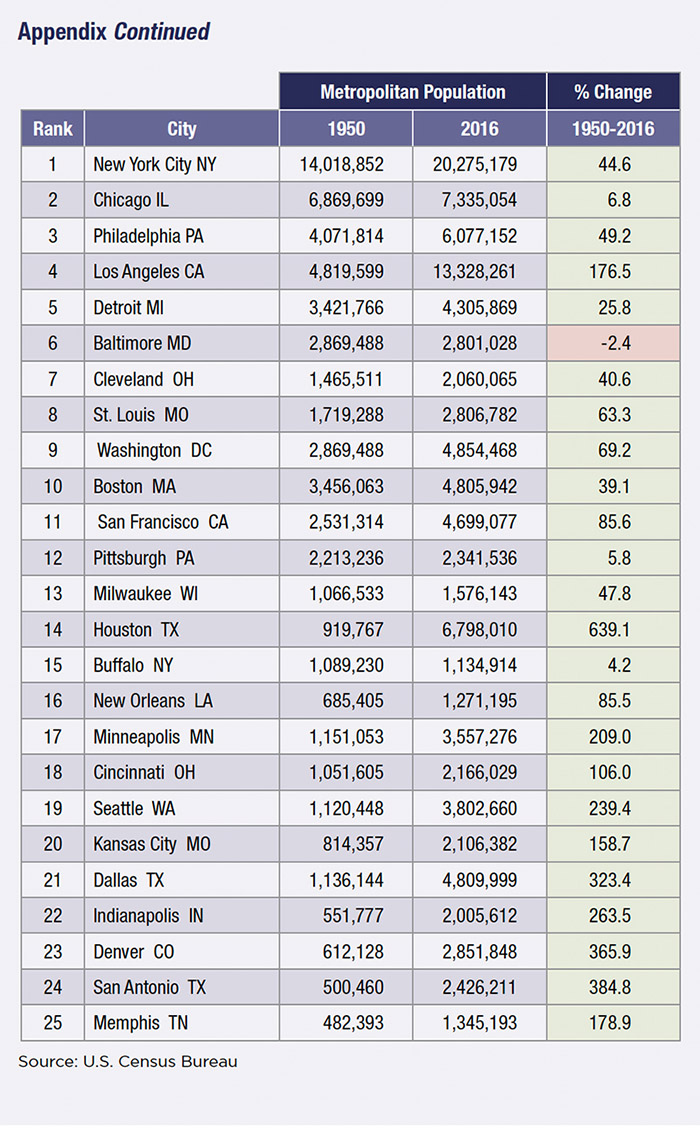

In 1950, Detroit was America’s fifth-largest city, with a population of 1.85 million people. By 2016, the city’s population had fallen 63%, to 673,000, dropping its rank to 23rd. Among the leading cities in 1950, Detroit’s loss of residents was perhaps the most severe, tied only with the much smaller St. Louis. The story of Detroit’s decline, while dramatic, is largely a mirror of what has happened over the last half-century to many older cities in the eastern half of the United States. From 1950 to 2016, with the exception of New York, every one of the 25 biggest cities in 1950 on or east of the Mississippi has lost population (see Appendix).

However, other than Baltimore (which has effectively merged with metropolitan Washington, D.C.), the metropolitan regions of all these shrinking cities have grown. If all of America’s struggling cities are actually in the midst of thriving regions, we need to reexamine the widely held view that their hollowing out is the inevitable result of irreversible economic and demographic trends.

The fundamental plight of Detroit, as well as all its peers in the eastern U.S., has involved not just the loss of population and jobs but the abandonment of the city, over many decades, by a large share of their middle-class families—who generally moved not to other parts of the country but to nearby suburbs.1 Of course, all cities in the U.S., even thriving ones, lose families to the suburbs, and the families with the greatest means and motivation to move are often found in the middle class. But in America’s healthiest cities—such as New York, San Francisco, Indianapolis, Seattle, Denver, and Portland—the number of newcomers moving in is equal to or exceeds the number of those who are leaving for the suburbs. In less dynamic cities, there are few newcomers to offset out-migrants.

The extent to which a city loses, or its suburbs gain, residents depends heavily on its attractiveness as a place to live. To draw and retain a solid majority of middle-class households, a city must be physically appealing, safe, and sufficiently amenity-laden to compete with its suburbs. While cities can’t match the suburbs for tranquillity, they have many offsetting advantages that, if attended to, are just as important in giving their residents a high quality of life: commercial and cultural vitality, urbane streetscapes, accessibility and convenience, and ethnic and social diversity, to mention a few. An encouraging trend in this regard: growing numbers of both younger and older Americans are moving back to the city just as many suburbs are becoming shabbier and more congested.2 Yet cities still face an uphill fight in their battle with suburbs to attract residents.

The World War II Watershed

Before the mid-20th century, city planning in the U.S. focused primarily on the design and installation of critical transportation infrastructure, public parks, and the siting of important public, cultural, and religious buildings. The planners’ transportation, utility, and public facility infrastructure not only established the framework that largely determined the cities’ physical form and character; it made them highly functional and capable of supporting dense concentrations of housing and commerce. Because of their superior infrastructure, American cities, before the wave of post–World War II suburbanization, were able to expand their municipal boundaries as their populations grew—as New York City (originally just Manhattan) did in 1898, when it absorbed the cities of Brooklyn and Staten Island, as well as portions of Nassau and Westchester Counties (Queens and the Bronx, respectively).

While pre–World War II planners designed their cities’ infrastructure, virtually all residential and commercial structures were built and financed by private developers with little public input. In many cities, local governments imposed limited design standards to protect health and fire safety, limited building-density standards to control congestion, and made sure that water supply and waste disposal were safe and sanitary. However, market forces essentially decided the design, location, and quality of commercial and residential development—whether commercial hubs, elegant residential neighborhoods for the growing middle and upper classes, or row houses and tenements for the working classes and poor. Industrial plants were located along waterways, railway lines, and major arterial roads to minimize cost and maximize profit.

Detroit’s emergence as a major city began with the help of good planning. First, in 1807, Augustus Woodward, the first chief justice of Michigan Territory, won authorization for Detroit’s radial downtown street plan, designed by Pierre L’Enfant, who earlier had laid out the streetscape of Washington, D.C. Later, with the redesign of Belle Isle park by Frederick Law Olmsted in the 1880s and the construction of the Detroit Public Library and the Detroit Institute of Arts, each designed by renowned architects, the Motor City joined the ranks of America’s most beautiful cities.

After World War II, as urban planning became increasingly professionalized and accepted as a government function, planners lost control of the design of city infrastructure. Federal and state governments began building highways to the suburbs, while cities began neglecting their infrastructure (unless subsidized by federal or state funds). And suburbs off-loaded the design and construction of their own street networks to local housing and commercial developers.

This model has mostly continued. Instead of designing urban infrastructure, planners now focus on influencing private development. They use zoning to regulate private property. They use eminent domain to acquire private property. And they use federal grants to subsidize, eliminate, or alter private property. The one common denominator here is that all these planning “tools” are explicitly designed to bend or thwart market-driven development.

Thus, the post–World War II planning paradigm turned the historical one on its head: henceforth, others would design and build the urban infrastructure that gives cities their shape and functionality, while city planners would substitute their judgment for that of the market when it comes to the design, placement, and economics of the homes, shops, and industries that constitute the lifeblood of cities.

Planning in City and Suburb

Planners in cities and suburbs implemented the new paradigm in radically different ways. In the suburbs, planners showed little interest in their communities’ overall design and infrastructure. Instead, they focused on preserving their community’s “suburban” character, including socioeconomic segregation, through zoning, a powerful tool for development regulation blessed by the Supreme Court in its 1926 Euclid v. Ambler decision. Zoning used in this way may be selfish and foster racial segregation, but it has worked to sustain the suburbs, especially upscale ones like Birmingham (Michigan), Wellesley (Massachusetts), and Clayton (Missouri), as highly desirable places to live.

In the cities, planners (in collaboration with municipal, state, and federal agencies) used federal funds to tear down old neighborhoods to make room for newer, supposedly superior, development. This was the era of “urban renewal,” and Detroit was among its leading practitioners.

The American Housing Act of 1949, in the name of “slum clearance,” invited cities to identify “blighted” residential and commercial neighborhoods, offering them funds to acquire, through eminent domain, large tracts of land in these areas, raze existing structures, and then sell the land at a deep discount to developers who promised to erect better housing and commercial buildings, or, using other federal subsidies, erect new low-income housing projects.

The steep decline of older U.S. cities coincided almost perfectly with the spread of the post–World War II planning paradigm. In contrast, Houston, the rare metropolis that was allowed to grow relatively organically, saw the biggest population increase of any big U.S. city during 1950–2016.3

Under former mayor Albert Cobo (1950–57), Detroit was an enthusiastic implementer of urban renewal, beginning with the city’s Gratiot Area Redevelopment Plan. The wholesale displacement resulting from this and subsequent urban renewal ventures destroyed entire neighborhoods—both the ones torn down and those affected by the influx of displaced residents. Because of its singularly harsh impact on African-American residents, urban renewal was one of the main triggers of the 1967 riots that greatly a ccelerated Detroit’s decline.

Another unfortunate aspect of urban renewal was Detroit’s decision to replace a perfectly functional downtown with glossy new skyscrapers and shopping malls, such as those at the Renaissance Center. In the process, thousands of viable, if unglamorous, businesses disappeared or moved, further hastening Detroit’s demise. The final nail in the city’s coffin was Detroit’s implementation of the interstate highway program, which, by slicing through large swaths of the city, destroyed even more homes and businesses.

Post-Urban Renewal City Planning

Fortunately, today’s urban planners have learned from some of the mistakes of the post–World War II model. For this, much credit is owed to Jane Jacobs, who, in 1961, penned the highly influential The Death and Life of Great American Cities, which challenged the beliefs and policies that characterized mainstream planning at the time.

Jacobs argued that older streetscapes, with their mix of stores and varied housing, are essential to neighborhood safety and social coherence and should be preserved and improved, not torn down. She believed that allowing expressways to slice through a city, as was then fashionable, was a disastrous mistake. Cities, Jacobs thought, are healthiest when allowed to remain eclectic, irregular, dynamic, and market-formed—filled with vibrant street life rather than centrally planned collections of bland towers and sterile shopping malls that turn their back on the street.

As Jacobs’s message seeped into the planning profession, city planners increasingly translated her critique into action. (Suburban planners, whom Jacobs largely ignored, have essentially retained all of the post–World War II suburban planning model.) Below are some trends.

Zoning

A move away from the rigid segregation of commercial and residential uses. Many zoning codes, in Detroit and elsewhere, now allow shops to locate among or near homes—for convenience and greater neighborhood vitality.

A move away from the rigid segregation of single- and multifamily housing. Many zoning codes now allow multifamily housing in single- and two-family districts. This responds to the declining appeal, especially among millennials and retirees, of living in single-family homes, the need to free up sites for multifamily housing in convenient locations, and a desire to generate greater neighborhood vitality.

A reconsideration of density constraints. Recognizing that higher residential and commercial density can be a good thing, especially in cities that have suffered or fear population decline, zoning-imposed density ceilings are being raised or eliminated.

Detroit and others are adopting, or considering, “form-based” zoning that sets specifications for new structures aimed primarily at their exterior form and their relationship to the street and neighboring structures. In many cases, these codes also do away with older kinds of use and density constraints.

Urban Renewal

Federally subsidized “raze and replace” urban renewal was ended by the Nixon administration in 1973. In its place, the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 (HCD) introduced Community Development Block Grants (CDBGs)—formula-driven allocations to cities and states for a wide variety of city and neighborhood improvement initiatives, with broad local flexibility in the selection of projects.

After the demise of old-style urban renewal, post-1970s large-scale city redevelopment projects are now undertaken through “public-private partnerships” with private developers. Under this rubric, planners work closely with developers in the design and siting of the projects, and cities use the power of eminent domain to acquire sites. Unlike old-style urban renewal, such projects typically have no federal subsidies or wholesale demolition of functioning homes or businesses, more mixed residential and commercial uses, and a much greater likelihood of economic viability.

Low-Cost Housing

HCD also effectively ended federal support for the kind of high-rise public housing projects that, together with federally subsidized slum clearance, had torn down established city neighborhoods to build dysfunctional complexes, such as Detroit’s Brewster-Douglass Homes (opened in 1938 and expanded in 1951).

By the time federal support for high-rise public housing ended, planners and housing advocates had sharply turned against it, especially after the demolition by explosives of the once-admired Pruitt-Igoe housing complex in St. Louis in 1972. In 1993, federal legislation launched the HOPE VI initiative, enabling local public housing authorities to tear down older high-rise complexes (like Cabrini-Green in Chicago) and replace them with low-rise, higher-amenity structures built in scale with their surrounding neighborhoods (Detroit demolished Brewster-Douglass Homes in 2013).

Since 1974, Section 8 of the Housing Act has authorized rental subsidies as the primary means of providing decent housing for low-income households.

Low-income housing has also been supported by CDBGs. In the 1980s, for example, New York City used billions of dollars of its CDBG allocation to acquire and restore more than 250,000 units of abandoned housing. It then turned their ownership and management over to nonprofit organizations.

Regarding City–Suburb Relations

One policy consequence of planners’ anti-sprawl campaign has been the promotion of rail and bus transit systems in medium-size and large cities. Since 1960, 37 U.S. cities have introduced light and heavy rail transit systems, and countless others have expanded their bus transit systems.4 Few of these transit initiatives, all heavily subsidized, have met their ridership expectations, and none has seriously impeded further suburbanization, but the new or expanded rail transit systems may have added to the appeal of inner-city living. However, Detroit’s entry into this venture, its “People Mover,” a three-mile elevated tram circling downtown launched in 1987, has done nothing to stem the city’s decline.

Aside from promoting city living as an antidote to suburbanization, planning orthodoxy now demands that suburbs “diversify” by encouraging more multifamily development and racial and economic integration. Development trends are moving in this direction, but this owes more to the “urbanizing” of the suburban housing market than to planners’ initiatives. By narrowing the perceived urbanization gap, these trends may make city living more acceptable in Detroit and other shrinking cities.

Rethinking City Planning

A key challenge now facing U.S. cities battered by population and job loss is to make them places where people want to live. In concrete terms, this means that these cities must focus on stemming further population loss and, in the case of Detroit and other severely depopulated cities, must aggressively foster repopulation. In this, they are in perpetual competition with their suburbs.

As noted, the great advantage that cities have over suburbs is their centrality—convenient access to downtown, with its jobs, institutions, and sports and cultural facilities. Beyond downtown, cities can still offer more urbane local shopping and dining, more diverse and interesting neighbors, and more varied housing than in the suburbs. On the other hand, Detroit and many other cities suffer from high crime rates, bad schools, and burdensome taxes.

In addressing these disadvantages, city planners can do only so much. They can shape and improve cities’ physical appearance and functionality, and that counts for a great deal. But public goods, such as safety and good schools, are beyond planners’ control. High taxes are not necessarily fatal, as shown by the continuing appeal of New York and other high-tax U.S. cities (as well as the many popular high-tax suburbs). But a high-tax city can survive only if it delivers prosperity and a high quality of life. What should planners do?

Respect the Market

Today’s planners may be more realistic and market-responsive than those immediately following World War II, yet too many city plans remain full of gauzy visions overly dependent on government micromanagement. In many parts of the city, zoning should be reformed to make neighborhoods and streetscapes more responsive to lifestyle and market preferences. Developers and property owners should be given more freedom to build according to their needs or what succeeds commercially. In many parts of the city, zoning can be reformed, as described earlier, to make neighborhoods and street-scapes more responsive to current lifestyle and market preferences, but any zoning changes should be kept simple and have the support of the residents and businesses that they affect.

Detroit is now at an inflection point. With thousands of acres of vacant land ripe for redevelopment, it would be unwise for Detroit’s planners to overprogram what should be built. Most new development will, and should, be residential. But the kind of housing (row homes, apartments, single family) or the type of tenure (owned or rental) should be left to the market. The same goes for new commercial development, especially outside downtown.

Given the Motor City’s fragility, planners should refrain from aggressively pushing “affordability.” The complex regulatory and financing arrangements that typically go with subsidized housing (e.g., tax credits, Section 8 subsidies, prevailing wage rules, eligibility requirements) would seriously slow redevelopment. Much of Detroit’s new housing will be affordable without subsidy, anyway. Further, the prospect of forced mixed-income occupancy might impede the marketing of unsubsidized units. Other city (and state) regulations on the books that make development more expensive, such as “local only” labor, should be waived, too.

Save Neighborhoods

Like physicians, planners should first do no harm. All U.S. cities have neighborhoods that are thriving. Such neighborhoods should not be undermined with unwanted municipal facilities—such as homeless shelters, correctional facilities, sanitation-transfer stations, or public housing. Their streets should be pothole-free and clean, with garbage picked up frequently, streetlights that work, and graffiti removed as soon as it appears. Where necessary, streets should be plowed in the winter. Cities also need to prevent foreclosed properties from spoiling entire neighborhoods, through rigorous enforcement of occupancy restrictions and prosecuting squatters and vandals. They can also use eminent domain or partnerships with nonprofit community-development corporations—as in Cleveland, Philadelphia, and Columbus—to acquire foreclosed properties and rapidly renovate and resell them.

To save money servicing Detroit’s vast stretches of abandoned housing (over one-third of the city’s acreage),5 former mayor Dave Bing (2009–13) considered fostering the relocation and densification of the city’s remaining residents by curtailing street maintenance, policing, and other services in largely vacant precincts. Popular outrage kept the strategy from being implemented, but the idea was wrongheaded on its face. For Detroit’s remaining neighborhoods to thrive, all neighborhoods, including the poorest and partially abandoned, must be well maintained. Some cost savings can be realized, as occurred under Bing, through better management and efficiency or, in the case of streetlights, by transferring responsibility to an independent authority. But the physical upkeep of neighborhoods should never be compromised.

Detroit’s planners should also work with municipal colleagues to promote greater neighborhood autonomy. Urban residents would likely welcome some control over their destiny, as do most suburbanites. Municipal decentralization for Detroit has gotten a bad name because of the apparent failure of the city’s Community Action Councils (CACs) under former mayor Coleman Young (1974–94). However, unlike the federally sponsored neighborhood advocacy embodied in CACs, the kind of decentralization proposed here would entail the devolution of specific neighborhood services (street maintenance, parks, sanitation, etc.) to sub-municipal governments, along with a portion of the property-tax base to pay for them.

Fill the Voids

Most of America’s declining cities have large tracts of underutilized land. Even thriving ones are pockmarked with derelict or abandoned properties, many near downtown or in other prime locations, especially waterfronts. The lowest-hanging fruit for planners is to pick and revive these areas. First, the city must obtain title to the properties. In most places, vacant or abandoned parcels may already be owned by the city through tax foreclosure. In other instances, they are owned by other governmental entities or banks. Development on vacant land can be expedited by assembling individual parcels into large land banks. When it comes to disposing of banked property, planners should resist the temptation to preemptively decide what should be built there and instead consult with real-estate professionals and builders as to what might be economically viable. Prospective developers (or homeowners) can then be invited to submit specific development bids, with properties going to the most financially sound projects.

As noted, one-third of Detroit’s 344,000 residential properties are empty lots or are occupied by vacant homes. The largest share of these parcels is adjacent to, or near, downtown. This is where Detroit’s repopulation should best begin. The good news: these areas should be the most attractive for developers to tackle: their closeness to downtown and their emptiness should make them the easiest to market; and once these areas are repopulated, there will also be demand for ancillary commercial space.

Further good news is that Detroit has already assembled the majority of city-owned vacant parcels into a land bank. The city should combine as many of these parcels as possible into large contiguous sites and recruit developers to build on them, a process already begun in the Brush Park area. Incorporating isolated parcels amid mega-sites may require the use of eminent domain, as well as the cooperation of county and state government, banks, and private owners.

Along with the redevelopment of vacant areas, Detroit has an opportunity to create brand-new high-quality neighborhoods. As neighborhoods are redeveloped and repopulated, the city can turn the rebuilt communities into “new towns in town,” giving them the kind of sub-municipal governance structure proposed earlier. Building in some level of local autonomy will hasten their redevelopment and will assure their long-term sustainability.

Welcome Gentrification

One of the great forces for urban revival is gentrification, the arrival of middle- or high-income residents into heretofore undesirable or dying neighborhoods. Gentrification is the antidote to the bane of declining cities: middle-class flight. Yet many cities fortunate enough to experience gentrification are ambivalent about, or hostile to, it when it appears. The most common complaint is that gentrification causes displacement of existing households. In reality, many such households typically leave before gentrification starts, part of a downward cycle of rising crime, resident flight, and declining economic vitality.6 Indeed, not only does gentrification tend to cause minimal displacement; gentrifying neighborhoods actually make life better for existing residents in many ways, such as less crime, better city services, and more shops and restaurants.

Parts of Detroit—mostly downtown and neighborhoods at the suburban frontier, such as Grandmont-Rosedale—are experiencing the first shoots of gentrification. It remains to be seen whether gentrification will make further inroads into other established neighborhoods. But whatever the extent of gentrification, Detroit’s residents and planners should welcome it.

Breathe New Life into Downtown

Past efforts to revitalize downtowns created dramatic skylines but also tended to hasten cities’ decline. Most planners today are wary of artificially breathing life into city downtowns. Instead, the best that planners can do is to take careful stock of their downtown’s assets—architecturally distinctive structures, public buildings, parks, monuments, and so on—and enhance and preserve them. Planners needn’t be concerned about coaxing or subsidizing office development: that is the one kind of downtown development that always takes care of itself.

The downtown attractions that planners can most easily have an impact on are major government, cultural, and transportation facilities, such as City Hall, museums, concert halls, and railroad stations. These typically belong to the city or are supported by it. Planners should make them as attractive and well maintained as possible. The cost of doing so can often be underwritten by philanthropic donors and conservancies. To lure residents downtown, a lot of restaurants, shops, and art galleries are needed, too. Cities such as Cleveland, Syracuse, and Portland (Maine) have created new dining and art districts on the edge of downtown and in former industrial and warehouse areas for this purpose.

As for downtown infrastructure and streetscapes: in most U.S. cities, these things have already been attended to. Indeed, downtowns in shrinking cities, more than those in thriving ones, have well-paved thoroughfares, spiffy street signs, good sidewalk paving, and more. The maintenance and further enhancement of downtown infrastructure should be left to self-funded business improvement districts.7 This saves cities money, and downtown merchants and property owners know best how to keep their districts attractive.

Detroit’s downtown is definitely “coming back,” much the way countless other city downtowns have revived. There has been substantial development and rehabilitation of office space, with most of it now occupied. There appears to be a burgeoning sector of tech and other “new economy” firms. Tourism has even picked up, spurred by the city’s downtown casinos. Government facilities have been renovated. Belle Isle, in the Detroit River across from downtown, is being upgraded. And new dining and crafts districts have sprung up on downtown’s edge. Detroit’s downtown streetscape is well maintained and attractive, with high-quality paving and strategically located landscaping.

Return to Planning the Public Domain

Planners should return to the work of their pre–World War II predecessors and focus on improving streets, parks, and public spaces. Most big U.S. cities, for example, have waterfronts. It is an appropriate function of planners to beautify them and make them accessible. If that means tearing down ill-conceived expressways, as Portland (Oregon) and Boston did, the long-run benefits will outweigh the costs. Likewise, parks are always among a city’s most important assets; one of the turning points in New York City’s recent revival was the rehabilitation of Central Park. Brownfield sites, restored with federal remediation funds, also offer an opportunity to create new public or private sites without displacement.8

Detroit has some of America’s best-designed parks, including several designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, the architect of Central Park. Keeping them lovely is well worth the cost. Beyond its largely revitalized downtown, Detroit’s planners appear to be focused on upgrading major thoroughfares, especially those radiating from downtown. However, a key prerequisite is rebuilding the secondary street and utility infrastructure across Detroit’s thousands of acres of vacant land, where roads are disintegrating.

Don’t Waste money on Smokestack Chasing

Many of the urban renewal efforts discussed earlier were paid for with federal tax dollars. More insidious, from the perspective of cities, are failed revitalization initiatives that cities themselves pay for—chiefly through tax abatement—under the misnomer of “economic development.” Chief among these are “smokestack chasing” and subsidizing sports arenas.9 Numerous economic studies have shown that such efforts almost always cost more in subsidies than they reap in economic gains—especially since tax abatements for a wealthy few inevitably require tax increases for the city’s other commercial and residential taxpayers.10

Instead of smokestack chasing, planners should focus on one of the true economic anchors present in virtually all U.S. cities: “Eds and Meds,” or colleges, universities, and hospitals. While many of the jobs in these industries pay less than old manufacturing jobs did, Eds and Meds are growing, high-skill industries that don’t despoil the local environment. Though Eds and Meds don’t pay property taxes, they still enrich the local tax base indirectly through economic spillovers. Planners should help Eds and Meds expand, and they should guide their expansion in a way that functionally and visually enhances the immediate surroundings.

Unfortunately, Detroit is engaged aggressively in smokestack chasing, generally in the form of long-term tax abatement, with much of it tied to Quicken Loans, a major local employer. As for Eds and Meds, the Motor City is home to the Detroit Medical Center, Wayne State University (one of Michigan’s largest universities), a branch of the University of Michigan, and numerous other health-care facilities and colleges. Altogether, Detroit’s Eds and Meds account for over 25% of the city’s 240,000 jobs.11

Have a First-Rate Planning Department

Among the most underappreciated functions of big-city planning departments is their collection and analysis of a broad array of data relevant to planning and governing cities. The best planning departments are superb at demographic analysis. And they keep careful track of key aspects of city functioning, such as traffic counts, sanitation volumes, housing-code violations, the condition of buildings, and employment trends by industry. Accurate data and analysis can have a highly beneficial impact on planning—though planners should avoid the temptation to use the data to micromanage decisions that are best left to private individuals and businesses.

Another capability of the best planning departments is their facility in sophisticated mapping and visualization. With modern computer technology, planners can generate interactive maps and three-dimensional streetscape images that instantly portray any section of their city as it currently is and can also assess the visual impact of potential alterations.

Spurred by current mayor John Duggan, Detroit has built a stellar planning department, headed by Maurice Cox. The staff, which has grown sixfold since 2014, is well trained and highly motivated. To the extent that planning can make a serious difference in restoring a declining city, Detroit is, for now, in very good hands.

Use Planning Tools Wisely

The planner’s tools today are not very different from those wielded in the past. The three main ones are:

- Zoning is the most comprehensive and powerful tool. “As-of-right” zoning determines what uses can exist, the density of development, and the exterior configuration of structures. Yet under the “Euclidian” (from Euclid v. Ambler) framework governing most American zoning ordinances, “higher” uses can locate in “lower” use zones: i.e., single-family homes can be built in multifamily zones, or stores can be placed in industrial zones. But cities can depart from the Euclidian framework and create “exclusive” zones, or they can, as described earlier, jettison established zoning features in favor of “form-based” zoning. In high-demand cities like New York, many newer residential and commercial buildings are not built under as-of-right zoning. Instead, developers are invited to seek waivers, especially for rules affecting density or building height, in exchange for including, or paying for, public benefits, such as affordable housing, public plazas, subway station upgrades, and more.

- Eminent domain gives government the power to acquire private land for a public purpose. Eminent domain can be especially useful in cities with large tracts of derelict properties or in those that want to modify the infrastructure grid or rehabilitate neglected or foreclosed properties.

- Community Development Block Grants. Every large American city receives a sizable grant each year from this federal program. Cities have almost unlimited discretion in how they use CDBGs, which are best used for improving infrastructure and other long-lasting public amenities. Cities can also distribute some of their CDBGs to neighborhoods when implementing decentralization initiatives.

While Detroit’s planning department has advanced sensible zoning reforms, state law vests zoning authority in an independent City Zoning Board, which must approve proposed changes. Based on the author’s discussions with the staff, the planning department expects approval of its recent zoning recommendations. Eminent domain, long misused in Detroit for previous urban renewal schemes, could nevertheless be an important tool for acquiring foreclosed properties or privately owned holdouts in Detroit’s largely vacant and landbanked inner-city neighborhoods. Although Detroit planners claim that such use of eminent domain would be hampered by Michigan court decisions that limit what constitutes a “public use” under the state constitution, they should continue to pursue the matter. As for CDBGs, Detroit’s current allocation is $34 million annually. Though not a large sum, it can still be a useful resource for well-placed infrastructure and public-facility improvements.

Looking Ahead

America’s large cities, even its most thriving ones, face serious challenges. For example, being home to ethnically and socioeconomically diverse populations can be a major asset, yet it also imposes considerable social integration and education costs. These cities also contain some of the country’s finest housing, as well as some of its worst. Their downtowns are home to much of their respective regions’ office employment, and they benefit from the growing Eds and Meds sector; but they have lost most of their manufacturing. Their extensive legacy infrastructure requires costly upgrading and retrofitting, too.

Many of the challenges facing U.S. cities are not new. But addressing them may be more difficult than in the past. With the exception of some Sunbelt cities, city boundaries have not expanded as their populations have spilled into the sea of metropolitan suburbs. This has placed cities in a fierce competition—for residents, businesses, and tax revenue—with their suburbs.

In the face of this competition, America’s thriving cities have remained attractive enough to retain or increase their populations and economic base. But the country’s shrinking cities have not been able to do this. If today’s urban planners concentrate their efforts on making cities more desirable places to live and do business, they can help Detroit and other once-great U.S. cities regain their historical vitality and ultimately prevail in the competition with their suburbs.

Endnotes

- See, e.g., John D. Kasarda et al., “Central-City and Suburban Migration Patterns: Is a Turnaround on the Horizon?” Housing Policy Debate 8, no. 2 (January 1997): 307–58.

- See, e.g., Richard Florida, “The Downsides of the Back-to-the-City Movement,” CityLab, Sept. 29, 2016.

- U.S. Census Bureau.

- American Public Transportation Association, “2017 Public Transportation Fact Book,” March 2018.

- Larry Gabriel, “Detroit’s Vacant Lot Problem,” Detroit Metro Times, June 6, 2018.

- See, e.g., Lei Ding and Jackelyn Hwang, “The Consequences of Gentrification: A Focus on Residents’ Financial Health in Philadelphia,” Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, July 2016; Lance Freeman, “Displacement or Succession? Residential Mobility in Gentrifying Neighborhoods,” Urban Affairs Review 40, no. 4 (March 2005): 463–91; Ingrid Gould Ellen and Katherine M. O’Regan, “How Low-Income Neighborhoods Change: Entry, Exit and Enhancement,” Regional Science and Urban Economics 41, no. 2 (March 2011): 89–97; Terra McKinnish, Randall Walsh, and Kirk T. White, “Who Gentrifies Low-Income Neighborhoods?” Journal of Urban Economics 27, no. 2 (March 2010): 180–93.

- A business improvement district is an area where local stakeholders oversee and fund the maintenance, improvement, and promotion of their commercial district. See, e.g., NYC.gov, “Business Improvement Districts.”

- Brownfield land refers to previously developed land that is not currently in use.

- “Smokestack chasing” is the practice of bribing firms by offering financial incentives, such as tax abatements, to move to, or remain in, a city.

- Alan Peters and Peter Fisher, “The Failures of Economic Development Incentives,” Journal of the American Planning Association 70, no. 1 (Winter 2004): 27–37; Timothy Bartik, “A New Panel Database on Business Incentives for Economic Development Offered by State and Local Governments in the United States,” W. E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, February 2017.

- “Demographic and Labor Market Profile: Detroit City,” Michigan Department of Technology, Management and Budget, April 2015.

______________________

Peter D. Salins is a senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute

This article is republished with permission from our friends at the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research.

Utah Standard News depends on the support of readers like you.

Good Journalism requires time, expertise, passion and money. We know you appreciate the coverage here. Please help us to continue as an alternative news website by becoming a subscriber or making a donation. To learn more about our subscription options or make a donation, click here.

To Advertise on UtahStandardNews.com, please contact us at: ed@utahstandardnews.com.

Comments - No Responses to “Report: Rethinking Urban Planning in Detroit”

Sure is empty down here...