Part 89 United States Drug Enforcement Administration Releases 2015 National Drug Threat Assessment Summary for Illicit Finance – Money Laundering, Transnational Criminal Organizations, Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, Mexico, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Florida, Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, and Caribbean, bitcoin, Dark Web Marketplace, Black Market, China, Philippines, and Latin America. Casino. Smuggling DEA ICE FDA

[2015 Drug Threat Assessment Continued from Part 88 Phencyclidine (PCP)]

2015 National Drug Threat Assessment Illicit Finance & Money Laundering

The US Drug Enforcement Administration 2015 National Drug Threat Assessment (NDTA) is a comprehensive report of the threat posed to the United States by the trafficking and abuse of illicit drugs, the nonmedical use of CPDs, [Controlled Prescription Drugs] , money laundering, TCOs [Transnational Criminal Organization] , gangs , smuggling, seizures, investigations, arrests, drug purity or potency, and drug prices, in order to provide the most accurate data possible to policymakers, law enforcement authorities, and intelligence officials.

Part 89 United States Drug Enforcement Administration Releases 2015 National Drug Threat Assessment Summary for Illicit Finance & Money Laundering, Transnational Criminal Organizations, Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, Mexico, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Florida, Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, and other islands in the Caribbean, bitcoin, Dark Web Marketplace, Black Market, China, the Philippines, and Latin America. Casino.

Overview Illicit Finance & Money Laundering

As federal money laundering laws become more stringent and financial institutions implement enhanced anti-money laundering measures, TCOs are increasingly creative in their efforts to evade laws and regulations. TCOs employ a wide array of money laundering tactics to move drug proceeds into, within, and out of the United States. However, the more commonly used methods have remained the same over the past several years. These methods include: bulk cash smuggling, trade-based money laundering (TBML), black market peso exchange (BMPE), structured deposits, and money transmissions.xxvii

Money transmissions are ways of transferring funds domestically or internationally via money transmitting businesses outside of the conventional financial institution system. These include but are not limited to: wires, checks, drafts, facsimiles, or couriers.

Currently, bulk cash smuggling is still the most widely-reported method used by TCOs to move illicit proceeds. In 2014, law enforcement officials reported over 4,000 bulk cash seizures to the NSS totaling over $382.2 million in US Currency (USC).xxviii

The information reported to NSS by contributing agencies may not necessarily reflect total seizures nationwide.

California, New York, and Florida reported the highest dollar amounts in seizures for a combined figure of $172.6 million. This was the first time since 2011 that Texas was not reported as one of the top three states for bulk currency seizures. Seizures in New York also dropped significantly, from $100.7 million in 2013 to $28.4 million USC in 2014. (See Table 14.)

(U) Table 14. Top 3 States for Bulk Currency Seizures,

2011 – 2014

Rank 2011 2012 2013 2014

1 CALIFORNIA NEW YORK NEW YORK CALIFORNIA

$134,666,241 $212,069,936 $100,779,781 $124,393,673

2 NEW YORK CALIFORNIA CALIFORNIA NEW YORK

$89,340,689 $132,274,001 $91,579,306 $28,450,308

3 TEXAS TEXAS TEXAS FLORIDA

$77,561,314 $66,797,740 $38,019,137 $19,934,742

Source: National Seizure System Data as of January 26, 2015

• California: Throughout California, illicit proceeds are primarily transported as bulk currency from Northern California to Southern California and Mexico via privately-owned vehicles and tractor trailers. Investigative reporting and currency seizures indicate Mexican TCOs routinely transport large sums of currency from the United States to Mexico via tractor-trailers. Due to the large volume of tractor-trailers crossing the US-Mexico border, Mexican TCOs are reportedly under the impression that this method of transporting bulk currency is minimally detected by law enforcement. Alternatively, couriers transporting money back to Mexico deliberately cross the border on foot during times and at locations with long waits to avoid law enforcement scrutiny. Some couriers declare bulk currency at the border, where it is difficult for officials to count large quantities of cash on a regular basis. Couriers traveling into the United States often declare more cash than on hand. The inflated declaration form is used to legitimize the origin of additional proceeds available in the United States when depositing the funds into bank accounts. Bulk cash is also seized from arriving airline and train passengers, as well as from parcels shipped to destinations in California from other domestic and international locations. Sixty-four bulk currency seizures were conducted at the San Francisco International Airport (SFO) and its mail and parcel facility during the first half of CY 2014. The seized monies, totaling $2.8 million USC, were suspected drug sales proceeds or payments for drugs. Of this amount, $2.4 million USC was confiscated from arriving airline passengers. TCOs use couriers to travel to and from the Los Angeles area by domestic airline carriers. Many couriers smuggle currency in luggage, carry-on bags, and via body carry. One example of a concealment method was a checked-in suitcase with a false bottom made from the cutout exterior of another roller suitcase. The suitcase was filled with men’s clothing and behind the false bottom was a towel and large amount of cash sealed in a heat/ vacuum sealed plastic bag. Reporting in the Los Angeles area also suggests unwitting legitimate trucking companies are used to facilitate the transportation of illicit-drug proceeds.

• New York: Bulk cash shipments were reported from New York to: Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Florida, Mexico, Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, and other islands in the Caribbean. In the Albany area, bulk currency shipments are often en route to Canada when seized. Bulk cash proceeds are transported in courier luggage or clothing and sometimes co-mingled with legitimate goods in containerized cargo. For example, automobiles shipped to the Dominican Republic are used to conceal bulk cash. Airline employees may also serve as money couriers from New York City to the Dominican Republic. Extensive enforcement actions regarding bulk seizures of cash in vehicles, apartment buildings, and storage facilities were common in the most recent reporting period. Colombian, Dominican, Jamaican, Lebanese, and Mexican trafficking organizations were involved in money laundering activities in New York. Dominican traffickers are typically involved in money pick-ups/drops. Local drug traffickers, particularly involved in the marijuana trade, often store drug proceeds at warehouses and stash houses before they are smuggled outside the region.

• Florida: Similar to other regions of the United States, bulk currency is commonly transported from South Florida to the Southwest Border in tractor trailers and private vehicles. Bulk currency is also shipped via commercial cargo vessels departing South Florida ports. The majority of bulk currency is seized through investigations or traffic stops. Bulk currency interdictions occur mainly along the I-10 (along the Florida panhandle), I-75, and I-95 corridors, as bulk currency is sent toward the Southwest Border, Atlanta, or East Coast cities.

Trade-based money laundering (TBML) continues to be a commonly used method to disguise illicit proceeds. TCOs launder proceeds through trade transactions to make the origins of the illicit funds appear to be legitimate. TBML is an attractive means for money launderers because it can bring in a high profit and offers low risk of detection from authorities. The complexity of TBML schemes is only limited by the means and capabilities of a TCO. Common TBML schemes include bartering (commodity-for-commodity exchange) and invoice manipulation by over/under invoicing merchandise or services.

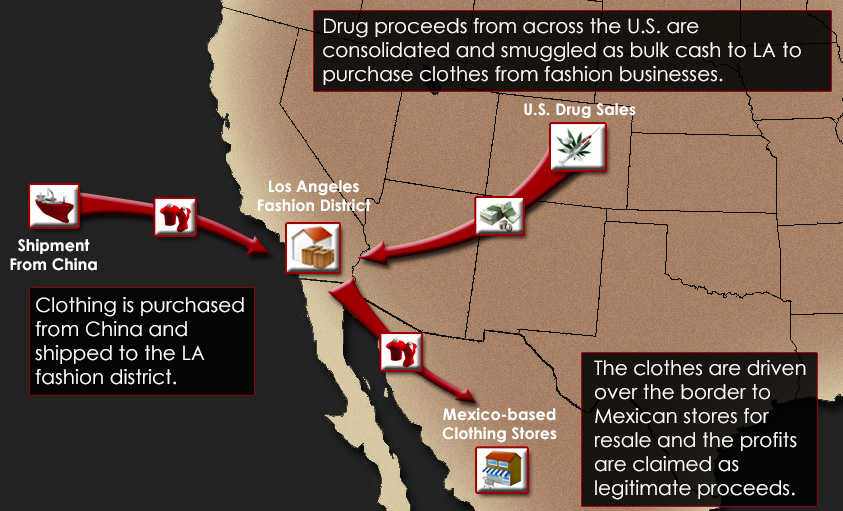

• Los Angeles: In September 2014, federal and local law enforcement authorities seized over $65 million USC and arrested nine suspects during an operation to disrupt the Sinaloa Cartel’s exploitation of the Los Angeles fashion district for TBML. The Sinaloa Cartel used US drug proceeds to purchase clothes imported from China that were stored in the targeted fashion businesses’ warehouses. The clothes were then shipped across the border into Mexico for resale and the profits placed into the Mexican financial system as legitimate proceeds. The Sinaloa Cartel also used these warehouses to store bulk cash until couriers working for Mexico-based fashion stores arrived with an invoice for the cash and drove it across the Southwest Border. (See Map 16.)

(U) Map 16. Trade-Based Money Laundering Scheme Exploits Los Angeles Fashion District

Drug proceeds from across the U.S. are consolidated and smuggled a bulk cash to LA to purchase clothes from fashion businesses. Shipment from China. Los Angeles fashion district Mexico based clothing stores. Clothes are driven oh Mexico for resale, profits claimed as legitimate profits. Source: Drug Enforcement Administration

The Black Market Peso Exchange (BMPE) continues to be a popular money laundering method, particularly with Latin American TCOs..

A form of TBML, the BMPE was pioneered by Colombian TCOs in the 1980s. Mexican TCOs began using the BMPE method along the Southwest Border shortly thereafter and its use has grown in response to Mexico’s anti-money laundering (AML) regulations governing the use of US currency within Mexico. This method eliminates the risk associated with bulk cash smuggling while, at the same time, lending illicit funds an air of legitimacy.

• In 2014, the BMPE continued to be a top money laundering method in metropolitan cities throughout California, Georgia, Florida, New York, and Texas. Money brokers operating mainly out of Bogotá and Cali, Colombia coordinate money pickups in the continental United States, Central America, and Europe. The money brokers drop off or wire millions of dollars to hundreds of electronics and computer companies in the United States. These companies co-mingle the illicit money with legitimate merchandise sales. The money is ultimately repatriated to TCOs in Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela through the sale of equipment.

Virtual currencies, such as the popular crypto-currency Bitcoinxxix, are quickly evolving economic tools that attract TCOs eager to exploit the often unregulated and decentralized virtual currency markets. For the purpose of this report, the accepted practice nomenclature for writing the word ‘Bitcoin’ is used throughout (en.Bitcoin.it/wiki). Therefore, when referring to Bitcoin as a protocol, software, or community, the word will be capitalized and singular: Bitcoin (e.g., The money launderer exploited Bitcoin to move drug proceeds). If referring to the units of currency a lowercase ‘b’ is used and the word is plural: bitcoins (e.g., The money launderer moved bitcoins to the TCO account).

Though still not a mainstream form of commerce, virtual currencies are increasingly accepted by large international businesses and could attain a much-improved stabilization in price despite falling market values. As with any new technology, there is a growing exploitation of virtual currencies by criminal organizations. In response, the US Department of Justice charged the unlicensed money transmitter Liberty Reserve and prosecuted the owner of the web-based marketplace Silk Road, which dealt almost exclusively in Bitcoin and connected drug traffickers with users.

Though the price of Bitcoin continued to decline during 2014, an increasing number of major stores and websites accept Bitcoin as a viable currency.

[95]

This list includes global online retailers, major clothing chains, restaurant franchises, international electronics companies, and many others, particularly new web-based businesses. Working closely with Bitcoin exchangers, these companies can resell the bitcoins for fiat currencyxxx before any price changes occur. A fiat currency is a currency that a government has declared as legal tender [ed. usually stated as all debts public and private, especially for paying taxes] . As more businesses embrace virtual currencies as acceptable forms of payment, virtual currencies should attract more users and, in turn, more investment. This could help stabilize the rate of exchange, and large withdrawals or deposits will not wildly affect the price.

Though the United States continues to improve its requirements for businesses and individuals dealing in virtual currencies, no overarching international regulation of virtual currencies exists. In March 2013, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) provided some enforcement oversight, later followed by further guidance in January 2014. FinCEN defined all businesses engaged in the exchange or movement of virtual currency to be money services businesses (MSBs), which must adhere to regular MSB requirements stated by the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). In March 2014, the Internal Revenue Service classified virtual currency as a property for tax purposes, applicable to all past and future transactions.

(U) Splintering Dark Web Marketplace Illicit Finance & Money Laundering

Silk Road, the original dark webxxxi marketplace for drugs and other contraband, was shut down in 2013 by the US Department of Justice. The dark web is the portion of the Internet that cannot be found using a regular search engine. Though many methods exist for building a dark web page, only certain search engines created for dark web browsing can access it. However, in the following month, Silk Road 2.0 was quickly established. Like its predecessor, Silk Road 2.0 was located on the dark web, difficult to access, featured increased user anonymity, and sold a variety of contraband, including illegal drugs. Continuing its enforcement actions against these illicit web marketplaces, the US Department of Justice also shut down Silk Road 2.0 in November 2014, and arrested its alleged owner.

The dismantling of Silk Road 2.0 has splintered the dark web drug market into numerous emerging websites. This rapid increase in successor websites presents new challenges for law enforcement to track and follow the sale and purchase of drugs on these markets as users seek alternatives that provide higher levels of anonymity.

For example, Evolution, an online marketplace website launched in early 2014, gained higher levels of use than either Silk Road website and boasts over 22,000 product listings of contraband items such as drugs, weapons, counterfeit documents, and stolen credit cards. Evolution permitted the use of Bitcoin for purchases and offered multi-signature transactions and an escrow service to promote user confidence in the security of transactions. However, on March 18, 2014, Evolution suddenly closed and its owners absconded with users’ bitcoins, valued at potentially over $12 million. This scam exposed the risks of selling/buying anonymously on the dark web and may increase user caution that will make it more difficult for law enforcement to penetrate these hidden illicit networks.

The continued growth and acceptance of virtual currencies has contributed to increasing exploitation by criminals seeking to sell illegal drugs in the United States. Reporting indicates Colombian TCOs may be using Bitcoin as a tool to conduct TBML schemes between the United States and Colombia. TCOs purchase bitcoins in the United States with drug proceeds and then buy merchandise from the wide range of US-based businesses that accept bitcoins. The merchandise can include phone and Internet minutes, tickets for events or travel, clothes, or luxury items. The merchandise is shipped to Colombia for resale as in a traditional TBML scheme.

Other Money Laundering Methods used by TCOs Illicit Finance

• TCOs continue to exploit the banking industry to give illicit drug proceeds the appearance of legitimate profits. Money launderers often open bank accounts with fraudulent names or businesses and structure deposits to avoid reporting requirements. TCOs contract individuals to deposit cash drug proceeds in increments below $10,000 USC into numerous bank accounts.xxxii The Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) requires financial institutions to file Currency Transaction Reports (CTRs) for deposits, withdrawals, exchange of currencies, or other payments in currency of $10,000 or more. Once deposited, the funds are electronically wired to other locations around the world.

• The use of money remitters remains a common method for laundering drug proceeds and sending payments for drug shipments.xxxiii

Money remitters fall under money service businesses (MSBs), which are non-financial institutions that transmit or convert money. According to FinCEN, MSBs include currency dealers or exchangers, check cashers, issuers of traveler’s checks, money orders or stored value, seller or redeemer of traveler’s checks, money transmitters, and US Postal Services. TCOs in the Boston area reportedly use money remitters to send money to Colombia and the Dominican Republic in amounts under $10,000. Heroin TCOs in Oklahoma City are reportedly sending drug proceeds to Mexico on a frequent basis through money remitters.

• Purchasing real estate and businesses is a prevalent method used to launder drug proceeds. Typically, illicit proceeds are deposited in a domestic or foreign bank, a limited liability company (LLC) is formed to buy property, and the money is wired to the title company or a cashier’s check is supplied for a cash closing. Purchasing properties under a LLC can obscure the identity of the actual owner(s) or the person(s) controlling the property. A quitclaim deed is a legal instrument that releases a person’s right to real property, title, or interest to another party without providing a guarantee or warranty of title.

• In recent years, the casino industry has been the subject of multiple federal investigations for various money laundering issues. The exploitation of casinos for money laundering has increased as US casino companies have expanded internationally, opening branches in China, the Philippines, and Latin America. These companies generally allow funds to be deposited in one of their casinos and then used or withdrawn as winnings in another. Money launderers exploit this system by placing or structuring drug proceeds into a US casino and then withdrawing the money at an international branch. Another tactic is to purchase chips with illicit cash proceeds, gamble, and then exchange the chips for a cashier’s check. The illicit proceeds now appear as legitimate winnings without raising much suspicion.

(U) TCO Member Sentenced to 150 years in Prison for Drug Money Laundering & Illicit Finance

In June 2014, Spanish national Alvaro López-Tardón was convicted in Miami, Florida on 14 federal counts to launder $26.4 million in drug proceeds from selling thousands of kilograms of cocaine in Spain. Three months later, López-Tardón was sentenced to prison for 150 years on 13 money laundering charges and one charge of conspiracy. The judge also imposed a $2 million fine and allowed the US Government to seize $14.4 million worth of property from López-Tardón.

López-Tardón purchased high priced cars, jewelry, watches, and real estate properties in Miami. Among the properties were 14 condominium units mostly purchased by LLCs, including López-Tardón’s residential penthouse in South Beach. According to court records, Fabiani Krentz purchased five units and transferred them through quitclaim deeds to companies owned by López-Tardón.xxxiv Krentz purchased and managed Miami properties, on behalf of the TCO of which López-Tardón was a member, to “legitimize” the TCO’s earnings from cocaine sales.

Disclaimer: The author of each article published on this web site owns his or her own words. The opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed by the various authors and forum participants on this site do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints of Utah Standard News or official policies of the USN and may actually reflect positions that USN actively opposes. No claim in public domain or fair use. © Edmunds Tucker. UTopiAH are trade marks of the author. Utopia was written in 1515 by Sir Thomas More, Chancellor of England.

[2015 Drug Threat Assessment continues next at Part 90 Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands, Guam, Tribal lands]

Utah Standard News depends on the support of readers like you.

Good Journalism requires time, expertise, passion and money. We know you appreciate the coverage here. Please help us to continue as an alternative news website by becoming a subscriber or making a donation. To learn more about our subscription options or make a donation, click here.

To Advertise on UtahStandardNews.com, please contact us at: ed@utahstandardnews.com.

Comments - No Responses to “Part 89 United States Drug Enforcement Administration Releases 2015 National Drug Threat Assessment Summary for Illicit Finance – Money Laundering, Transnational Criminal Organizations, Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, Mexico, Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Florida, Pennsylvania, Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, and Caribbean, bitcoin, Dark Web Marketplace, Black Market, China, Philippines, and Latin America. Casino. Smuggling DEA ICE FDA”

Sure is empty down here...